Today we travel to the quaint town of Iwatsuki in Saitama Prefecture. Iwatsuki is today Japan’s largest producer of traditional dolls employing over over 300 doll-makers creating miniature masterpieces using only natural materials since the 17th century, a tradition that continues to this day. Just like manga or anime that appeals to the young and old alike, these Japanese dolls from Saitama are loved by people of all generations.

My fascination with dolls started in my childhood years when I visited the Children’s Museum in Kolkata. I was deeply touched by the depiction of the story of Ramayana in a series of figurines behind glass panes. Even as I transitioned to adulthood, my love for collecting and cherishing figurines depicting local culture never waned. To this day, I take immense delight in my figurine collection procured from different parts of the world.

The name of “Saitama” originates from the Sakitama (埼玉郡) district. Sakitama has a long history and even finds a place in the famous Man’yōshū (万葉集), the oldest existing collection of Japanese poetry, compiled sometime after 759 CE. The colloquial pronunciation gradually changed from Sakitama to Saitama over the years.

Train from Takasaki to Iwatsuki

We were staying at the Toyoko Inn at Takasaki. From Takasaki, we took the Joetsu Shinkansen to Omiya, the biggest city near Iwatsuki. The Shinkansen does not go all the way to Iwatsuki so we had to change to the local Tobu-Noda Line at Omiya Station. From Omiya, it’s just a 15-minute train ride to Iwatsuki. If you are in the Kanto region, it is a good idea to obtain the Tokyo Wide Pass, or in my case the JR Pass.

After a short ride on the local train, we arrived at Iwatsuki Station at 11 a.m. The Tougyoku Doll Museum is just a minute away from the station in a tranquil neighborhood.

History of Saitama Dolls

In Japan, dolls have been a part of everyday life since ancient times. Japanese dolls reflect the customs of Japan and over the centuries have developed in many diverse forms. The Japanese term for “doll” (人形) is constructed by combining two kanji characters, where the first character signifies “human” (人), and the second character denotes “form” (形).

The first Ningyō (dolls) in Japan were the Dogu and Haniwa. The Dogu, appeared in the Jomon period (10,000 B.C.E. to 300 B.C.E) as a prominent fertility symbol. It held immense significance for the Japanese populace, representing the fertility of the land, animals, and people, and therefore played a crucial role in society.

The Haniwa, unglazed terra-cotta cylinders and hollow sculptures were most likely influenced by the Chinese terra-cotta. The Haniwa dolls added a new dimension to the Japanese Ningyō, introducing the concept of protection. These two elements, fertility and protection became the two most important factors of the Japanese Ningyō over the centuries to come.

Later around the 7th century, simple dolls made from wooden planks were created to entrust them with protection against misfortune in the coming year, after which the dolls were floated away on rivers. Katashiro paper dolls are still used today in purification rites for the same purpose at Shinto shrines throughout Japan.

With the introduction of Buddhism following the end of the Kofun period, the use of the Haniwa and Dogu faded and a new form of Ningyō was introduced that later evolved into the Amagatsu and Hoko. Amagatsu and Hōko (Nos.2,3) are dolls designed to protect babies from any misfortune that may befall them. As time passed and the Ningyō styles succumbed to the effect of commercialisation. Due to this the Ningyō slowly lost its connection to fertility and protection and their importance shifted to the aesthetics side.

The doll town of Iwatsuki

Around 3 centuries ago, Eshin, a Buddhist image sculptor from Kyoto, devised a method of making dolls out of Paulownia wood powder using a technique called Tosokashira. The process involved mixing the paste of Paulownia powder and Shobunori (paste made from wheat starch). In addition to Paulownia wood, the abundance of high-quality water found on Iwatsuki also became essential in creating the Tosokashira mix. The technique was passed down the generations and is still employed today for making these detailed handmade dolls.

Iwatsuki has a very interesting connection with the Toshogu shrine of Nikko. About 366 years ago, Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu invited skillful carpenters from all over the country in order to build the Toshogu Shrine, a mausoleum of Tokugawa Ieyasu. In those days Iwatsuki used to be a small castle town on the Nikko-onari-kaido road between Nikko and Edo (Old Tokyo).

The workmen and artisans labored for the next couple of years to build the heavily ornate Toshogu Shrine. Iwatsuki and its outskirts were abundant with the finest Paulownia trees. Once the Nikko Toshogu Shrine was completed, some of the disbanded carpenters chose to settle down in and around Iwatsuki and began earning their living by creating household furniture.

Tougyoku Doll Museum

The history of Tougyoku museum runs parallel with that of the town of Iwatsuki. Founded in 1852 CE, the museum was started with the idea of protecting and furthering the indigenous art of doll-making in Iwatsuki. Today, the museum exhibits hundreds of dolls including some really historical ones like the Iwatsuki ganso kamishimo hina doll.

From the outside, the Tougyoku Doll Museum building looks like any other building and is easy to miss. An elevator took us up to the museum on the fourth floor floor. Out of the lift, we found ourselves in front of a dimly lit room.

No one was around at the entrance so we just put the admission money in a box and entered the premises. The admission cost is ¥300 per person.

The museum was empty barring one family. Many of the dolls here, date back hundreds of years and are truly works of art. It is also interesting to see how they have evolved over time.

Dolls in Tougyoku Museum

Near the entrance there are various nifty little dolls made of fabric hanging on strings, creating a sort of curtain. Some were in the shape of Owls, one of the very popular creatures in Japan. Some time ago I did research on the Owl superstitions among the Japanese.

Clay Dolls

The first section my eyes went to was these miniature clay dolls. Beside it were the words – “Hatsu uma“, the first day of the horse. In the old Japanese calendar, the first day of the horse falls at the beginning of February, which coincides with the first planting of rice for the year. A festival is held at the “Fox Shrine” to pray for a good and prosperous harvest. This little figure is dancing at that festival.

This is a miniature clay art cute little boy, with a happy facial expression, who is taking part in the same Hatsu uma festival. He is shown wearing a beautifully painted kimono, decorated with colorful flowers and is playing a Japanese taiko or drum.

Shichou dolls from Taisho period

On the left wall, the Shichou dolls are on exhibit from the Taisho era (1868-1926). These impressive samurai warrior dolls were crafted for display on Boys’ Day, celebrated annually in Japan.

The exquisite detailing of these works of art is beyond words. Extreme effort has been put into making the expressions so human.

Another doll from the same era.

Ichimatsu Dolls

Ichimatsu Ningyō dolls were widely loved by people as a typical cuddly toy-doll during the Edo Period (1603-1867) and remain popular today as a gift for girls and as an art object. It is said also that a newly married couple will be blessed with a healthy baby when they display this doll.

The widely held explanations regarding the origin of the name of Ichimatsu Ningyō the name came from Ichimatsu SANOGAWA, a kabuki actor in the mid-Edo period.

Ichimatsu Ningyō, which consists of a head and limbs made from the mixture of sawdust of paulownia wood and wheat starch, or from wood, painted with a white pigment made from oyster shells (or that made from clam shells), connected to a body made from a sawdust-stuffed cloth, is sold naked and the purchaser makes its costume. It ranges in size from as small as 20 centimeters to larger than 80 centimeters, but it is generally around 40 centimeters high. There are girl and boy dolls, and the girl doll has a bobbed hair transplanted and the hair of the boy doll is drawn with a brush.

Kokin-bina Dolls

Hara Shugetsu, a doll-maker in Edo (Tokyo), developed the Kokin-bina style during the Meiwa Era (1764-1772 CE). The style’s name comes from the Kokinshu, a Heian Period poetry anthology. Kokin-bina draws from several earlier doll styles. The Emperor doll usually wears a simple black ho, emulating the courtly style of the Yusoku-bina. The Empress doll is more like the Kyoho-bina style, as she typically wears an elaborate junihitoe, the twelve-layered court costume of the Heian Period, as well as a crown styled into a mythical phoenix. These inspirations show how doll-makers balanced competing tastes by pairing the austere formality of the Yusoku-bina with the elaborate textiles of the Kyoho-bina.

This is a rare Edo Period Kokin-bina Empress. It is part of a Dairi-bina Imperial Couple for the Hina-matsuri Girl’s Day celebration. The me-bina lady is wearing a spectacular crown. The dress is a formal court attire.

An important difference between the Kokin-bina and earlier doll styles was how they were manufactured. As the popularity of the Hinamatsuri festival increased, doll-making was divided into different specialties. Carefully sculpted heads were fashioned at a workshop in Edo and the simpler bodies, hidden under clothes, were mass-produced in Kyoto. The extra care given to the heads allowed for other innovations, such as the extensive use of inset glass for the dolls’ eyes. Once complete, the heads were shipped to Kyoto where they were painted, matched with a body, and dressed.

By the time the “Kokin bina,” shown below, became popular, it had become the tradition to display other dolls below the imperial pair. Among these were the Three Court Ladies (Sannin Kanjo) dolls and Five Musicians (Gonin Bayashi).

Hina Ningyō

From the Shichou dolls, we moved on to the most favorite of all dolls – Hina Ningyō. The Hina Ningyō dolls have a history of over 1000 years. There are quite a few types of the Hina Ningyō, the Amagatsu, Houko, Tachi Bina, Kan’ei Bina, Kyouho Bina, Jirozaemon Bina, Yuzoku Bina, Kokin Bina and the Muromachi Bina. However, the latter six dolls are all different types of the Dairi Bina, who respectively are evolutions of the Amagatsu and Hoko.

These dolls are made with extremely ornamental details and calm expressions. They usually represent the Emperor, Empress, and other court attendants of the Heian period (794-1185) During the Hina Matsuri festival, celebrated on March 3rd each year, families with the girl child display their Hina Ningyō dolls and pray for their child’s growth and happiness. Most Hina dolls are heavily ornate.

The carpenters did not just make dolls. They also created some exquisite furniture to go with the cute dolls. The miniature vessels and furniture are perfect for a doll house. Hina Dolls are traditionally displayed on March 3rd, the Girls’ Day held to wish for healthy growth and happiness of girls. In the Heian period (794-1192 C.E.), people made dolls with paper or grass, imbued them with misfortunes and bad luck they might suffer from, and then released them to rivers or the sea as their bodily substitutes. Separate from that, there were also paper dolls called Hina Dolls which aristocratic girls played with. With time, the customs of Hina dolls that were floated on water and those that girls played with were integrated to give birth to paper dolls and standing earthen dolls that led to the Hina Dolls of today.

These Hina always appeared in pairs, and these pairs would always be placed on the highest part of the Hina display. These Hina as pairs were called the Dairi Bina. Two of the most important dolls would most likely be the Houko and Amagatsu, which have been thought to be the predecessors of the Dairi Bina. The Houko and the Amagatsu are thought of as a pair, where the Amagatsu is the male equivalent while the Houko is the female one.

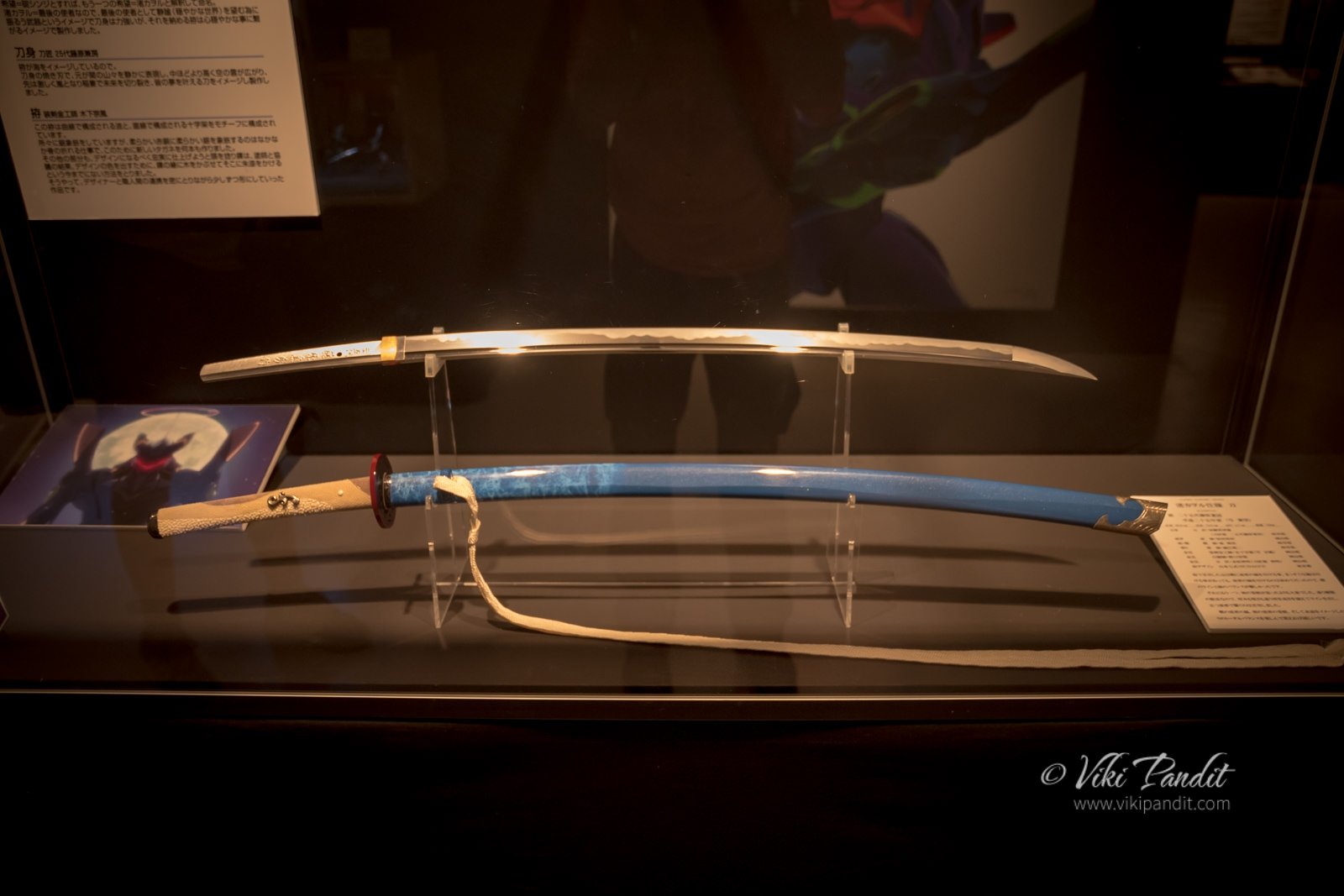

Gogatsu Ningyō

On Boys’ Day which is observed on May 5th, families pray for their sons’ good health and success. On this day, also known as Tango no Sekku, families display figures of costumed warriors with miniature armor and warrior helmets. These dolls especially made for boys are called Gogatsu Ningyō and appear with fierce expressions, wearing armor, and showing the courage, bravery, and honor expected of the Samurais. Models of armor and dolls of heroes are put on display for the festival, and rice-cake sweets wrapped in blades of bamboo grass or oak leaves are eaten in celebration.

Hero dolls that are particularly popular include Momotarō and Kintarō, both known for possessing super-human strength and for having saved the people by overcoming monsters.

Origin of Gogatsu dolls

The origins of Gogatsu dolls come from an age-old samurai tradition. In the old days, when a boy was born in the family of a samurai, his parents used to put ornamental helmets and trinkets and hang them at the entrance gate to celebrate his birth. They also had a custom of gifting a new samurai body armor to the child. These items were put together to form the Gogatsu doll, though in a smaller size. To this day people display Gogatsu dolls to protect their sons from evil and Koinobori (carp streamers) along with wishes for good health and social success.

Oyama Doll

Oyama Ningyō is the name given to traditional Japanese female dolls which are, for the most part, inspired by ukiyo-e images from the Edo period. These types of Japanese doll express a woman’s beauty through a gorgeous costume and elegant figure.

This kind of doll has been very popular since the Edo period, and it is also used for the Girl’s Festival held on March 3rd. When girls of the Samurai class got married, their parents gave them the Dressed Dolls as a ‘substitute’ that would consume possible misfortunes on behalf of the girls. For this reason, the dolls were crafted as women of high ranks.

As the crafting techniques evolved with time, the dolls today have come to be enjoyed by all people. Particular among them is the doll modeling a Japanese traditional dancer called Oyama Doll named after Jirosaburo Oyama, a renowned doll maker in the Edo period.

Most of the Oyama dolls are derived from Kabuki each representing a particular dance.

I totally loved the intricate details on the kimono of this doll.

Eto Dolls

Introduced from China in the period of Yin, an ancient dynasty that reigned around the 17th century B.C., to Japan, Eto is a cycle of sixty years that consists of twelve signs relating to animals and ten elements. Originating in China and spreading to Japan, Vietnam, Russia, and Eastern Europe, it was used in the calendar, as well as to indicate angles, time, and directions. When applied to the calendar, each year has one of the twelve signs of animals.

Thus the calendar has a twelve-year cycle. The order of years is; rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, rooster, dog, and boar. Each year, Japanese people place an Eto Doll of the animal of the year. They believe that the Eto Dolls absorb their misfortunes during that year.

After about an hour of going through some amazing history, we left the museum. Just across the street, opposite to the museum, one can find a souvenir shop that also has a huge collection of Hina and Gogatsu dolls for sale.

The biggest festival in Japan surrounding dolls is the Hina Matsuri, or the Doll Festival, even though the Hina Matsuri is still celebrated today the original meaning of the festival is lost to most Japanese people. In ancient times the Hina matsuri was about the cleansing of body and soul, but as it moved closer to modern times, it was the festivities and beauty of the festival that mesmerized the Japanese people

One of the cheaper ones can set you back by ¥200000.

The Hina dolls are kept on the 2nd and 3rd floors. Although the Hina display does not have a longer history than from the Edo period (1600-1868), the celebrations around it had been prominent since the Heian period (794-1185)

For the Japanese, these dolls enjoy a special place in their lives. In most countries, the term “doll” typically refers to playthings. However, in Japan, beyond being toys, Ningyō have evolved into forms of art, craftsmanship, and objects laden with wishes. There remains a prevalent belief in Japan that anything crafted in the likeness of living beings should be treated with respect. When someone can no longer keep a cherished doll, it is not discarded as waste; instead, it is dedicated to shrines or temples, where a Ningyō kuyo, or doll funeral service, is requested. This practice has endured since ancient times and continues to this day.

The ground floor has some nice cheaper souvenirs for tourists like us 🙂 Rummaging through the souvenirs I found a set of cards with hand-drawn paintings of 6 UNESCO sites in Japan. They looked beautiful. I had visited all barring the Nikko Toshogu Shrine. We decided right then to visit the shrine the next day.

I thoroughly enjoyed my time at the museum and the shop. I wasn’t carrying enough cash to own one of these from the shop today but I am really determined to come back one day to get one of these for my souvenir collection. After a fun morning, we were on our way to the Saitama Railway Museum.

1-3 Honmachi, Iwatsuki-ku, Saitama City

TEL: 048-756-1111

10 am to 5 pm (May 6th to October 31st)

10 am to 6 pm (November 1st to May 5th)

Mondays and Tuesdays (May 6th to September 30th)

Mondays (October 1st to October 31st)

Open every day (November 1st to May 5th)

*Temporarily closed 5/8/9 ·Ten

4F Higashitama Building, 3-2 Honmachi, Iwatsuki-ku, Saitama City

TEL: 048-756-1111

10 am to 5 pm

Adults: ¥300

Free: Elementary school students and younger Free

Free: Persons with a disability certificate with one accompanying person

Mondays and Tuesdays (May 6th to September 30th)

Mondays (October 1st to May 5th)

*Temporarily closed 12/31, 1/1, 5/6