Tsubosaka-dera Temple, situated in the serene landscapes of Nara, Japan, is a cultural gem with roots dating back over 1,300 years. Nestled on Mount Yoshino, this heritage site provides a panoramic view of the surrounding mountains and valleys, particularly breathtaking during the cherry blossom season.

Temples

The historic ramparts of Chitradurga Fort

Perched atop a cluster of picturesque hills in Karnataka, Chitradurga Fort is a formidable testament to the region’s historical legacy. Dating back to the 17th century, this massive fortification is renowned for its ingenious military architecture, featuring a complex series of concentric walls, bastions, and gateways.

The Dazzling White Temple: Wat Rong Khun

Wat Rong Khun, or the White Temple, is a contemporary Buddhist temple in Thailand, designed by artist Chalermchai Kositpipat. The temple is renowned for its unique design blending traditional Thai elements with modern artistic expressions.

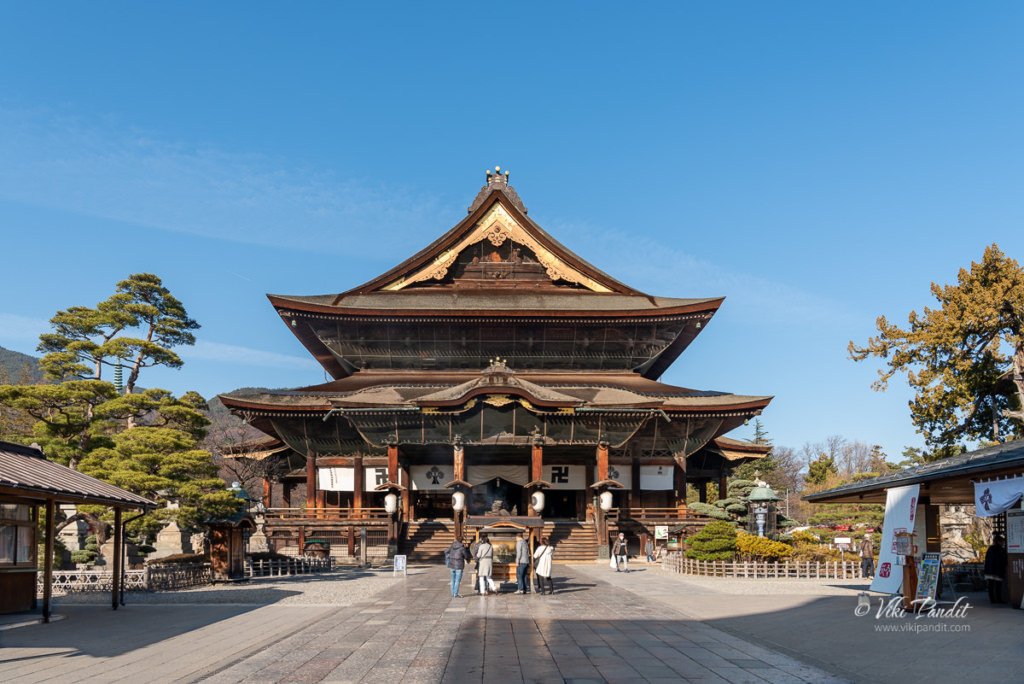

Zenkoji

Zenkō-ji is a Buddhist temple located in the city of Nagano, Japan. The temple was built in the 7th century. The modern city of Nagano began as a town built around the temple.

Great Buddha of Shoho-ji

The Gifu Great Buddha is a massive Buddhist statue located in Shōhō-ji in Gifu Prefecture of Japan. Completed in 1832 CE, it is the only Daibutsu created of wood and lacquer.

Praying for love at Izumo Taisha

Izumo-taisha, officially Izumo Ōyashiro, is one of the most ancient and important Shinto shrines in Japan. Located in the city of Izumo of Shimane Prefecture, the shrine is dedicated to the god of nation-building – Okuninushi-no-okami

Sunset at Nigatsu-dō

Nigatsu-dō is one of the important structures of the Tōdai-ji temple in Nara. If you are here to know more about Nigatsu-dō, you already must be familiar with the Todai-ji temple, registered as a world heritage site, and one of the most revered Buddhist temples in all of Japan. I have visited Nara Park many […]

Group of Monuments at Aihole

Today we drive to Aiholi, said to be one of the first regional capital of the Karnakata region under the rule of the Calukyas. The town contains a large number of early Hindu temples and shrines including some outside the walled site that mostly date from the 6th to 8th century CE when the city was at its zenith of prosperity and power.

Group of Monuments at Pattadakal

Pattadakal, also called Paṭṭadakallu, is a collection of temples from 7th and 8th century CE Hindu and Jain temples in northern Karnataka. Declared as a UNESCO World Heritage site, it is a historically significant cultural center and religious site to witness the structural tastes during the times of the Chalukya dynasty.